This review explores the new release of 4M’s IDEA, a BIM application for architectural design that is part of 4M’s multi-disciplinary BIM suite which also includes applications for building services and energy analysis. I last reviewed IDEA all the way back in 2010, and the new release, v.19, is a major one, representing a generational change to the 4M suite. Previously, it was based mostly on IntelliCAD, the low-cost DWG alternative to AutoCAD, but in the new release, the code has been completely restructured to work with the ODA (Open Design Alliance) engine, developed by the open-source DWG consortium of which 4M is an active founding member. 4M also continues to remain an active founder member of the IntelliCAD Technology Consortium (ITC), with which it has a common history of almost 20 years now, and it actively follows all the ITC developments that can be implemented in its products.

The updates to IDEA are across all areas of the application, including its interface and performance, modeling and rendering, phasing and estimating, and collaboration and interoperability. While some of these come to IDEA from 4M CAD, the 2D and 3D DWG platform on which its BIM applications are built, many of them are specific to building design. Let’s see what they are.

The most visible change in the new generation of the 4M BIM suite, including IDEA, is a new ribbon interface, which not only makes the applications in the suite more intuitive and easier to use but also brings them in line with modern applications that have transitioned to the ribbon interface. The individual tabs in the ribbons collect all the disciplinary tools for that application, and in the case of IDEA, this translates to separate tabs for drawing, general 3D modeling, architectural BIM modeling, rendering, annotation, viewing, etc. (Figure 1). While this interface makes it much easier for new users to navigate, the command line interface for expert users is still very much a critical component of the application. There is also the option of having all the toolbars with their individual tools visible, in the form of floating palettes, for existing users who may be used to them and prefer them to the ribbon interface. While these are visible in the default installation of the application, I found them somewhat overwhelming and simply turned them off.

Other interface enhancements in the new version of IDEA include expanded functionality of the Properties palette, which now also allows the BIM properties of a building element to be modified along with its CAD properties. In addition, it also allows selection in addition to editing object attributes, enabling you to select multiple entities in the model based on specific properties. So, for instance, in Figure 2, the selection option in the Properties palette has been used to select all the wall objects whose “Type” is specified as “Outer.” There are 142 such walls in the project, and now that they have all been selected, any changes to wall properties such as layer, material, insulation, etc. can be applied to all of them in one step.

Other new interface capabilities include the availability of grips in all the BIM entities in addition CAD objects to change graphically change their dimensions, orientation, etc. (Figure 3), and the addition of buttons for GRID, ORTHO, ESNAPS, etc., in the Status Bar, just like in AutoCAD, along with new buttons to control annotation scales and visibility.

On the performance front, the new generation of the 4M BIM suite is designed on a re-engineered 64-bit architecture and the ODA’s latest Teigha platform, which makes it noticeably faster, especially when opening and saving project files as well as for display functions such as zoom and pan.

All the applications in the 4M BIM suite, include IDEA, follow the main idea of BIM—creating the building model once and subsequently generating all the required building documentation, schedules, renderings, animations, etc., from it. The approach is centralized, making IDEA similar to Revit and ArchiCAD, where the model and all associated drawings and other related information are stored in a single file rather than distributed across multiple files such as in Bentley BIM or Allplan. The file size is, however, dramatically smaller and it is in the DWG format, which means that it can be directly opened by the large number of applications that can read DWG files. (However, the BIM entities in the file will not be recognized as building objects unless the model is exported to a building-specific format such as IFC.) When a new project is created, in addition to the DWG file that contains the model and drawing, IDEA automatically creates a project folder for it to hold the DWG file and any files exported from it such as renderings, reference files, IFC files, etc. For example, see Figure 4, which shows the Open Project dialog in IDEA providing a preview of the project called “Villa-19-1,” the actual folder of that project showing the main DWG files along with other associated files, and finally, the project opened in IDEA.

The actual definition of the building in terms of the number of levels and the height of each level is specified in the Building Definition dialog (see Figure 5). If the elevation or height of a level is changed, the changes are automatically propagated to the rest of the levels to maintain the building definition. There is also the option to automatically change the heights of walls and columns if the height of the level that they are created on is changed, thus maintaining the integrity of the model. This option was not implemented the last time I reviewed IDEA, and I am gratified to find that it is now available, strengthening the BIM capability of the application.

Once the levels have been defined, you can use the different tools in the Building Entities tab to model elements such as walls, doors, windows, slabs, roofs, staircases, beams, etc. on them. All the elements are created on the active level, which can be selected from the Building Browser located below the Properties panel. These levels are automatically created once the levels are defined in the Building Definition dialog. When a level is activated, it is shown in 2D by default, but a single button switches it to a 3D view. This is really helpful to quickly isolate a level and view it in 3D for modeling and editing entities on it (Figure 6).

While the actual modeling of building elements is similar to other BIM applications, some of the modeling enhancements in the new version of IDEA include the ability to model corner openings as quickly and easily as regular openings (Figure 7), expanded options for modeling stairs, the ability to trim wall heights to any shape (Figure 8), and new 3D object libraries for quickly populating models with furniture, foliage, and other entourage.

The photorealistic rendering capabilities of IDEA are provided by the PhotoIDEA module. It comes with a large library of real-world materials with textures such as marble, wood, stone, carpets, etc., that can be applied to objects and adjusted to render them as required. It also allows lighting sources, including the sun, to be positioned, and includes other settings such as background, fog, and the use of bitmap images to add as entourage to the rendering. You can choose from a number of different rendering options, starting from the quick OpenGL mode to higher-quality and more time-consuming settings that include lights, materials, and ray-tracing technology (Figure 9). Like any other visualization application, generating a good rendering in IDEA takes time, although improvements in the rendering algorithm in the new version reduce the time considerably. While the quality of the built-in renderings is not up the level of other established BIM applications, the fact that the model is in DWG format means that it can opened up easily in the multitude of dedicated rendering applications that read DWG files for highly photorealistic visualizations. Figure 9 includes an example of a rendering of the project created using a dedicated rendering application.

The other key feature of IDEA worth noting is the WalkIDEA module, which allows you to take a real-time virtual tour walkthrough of the rendered 3D model, walking both inside and outside it, and saving the virtual trip as an AVI file. It has several options for moving up or down staircases, opening doors, and so on. In addition, WalkIDEA can also offer the experience of a 4D stereoscopic reality through a pair of stereo glasses.

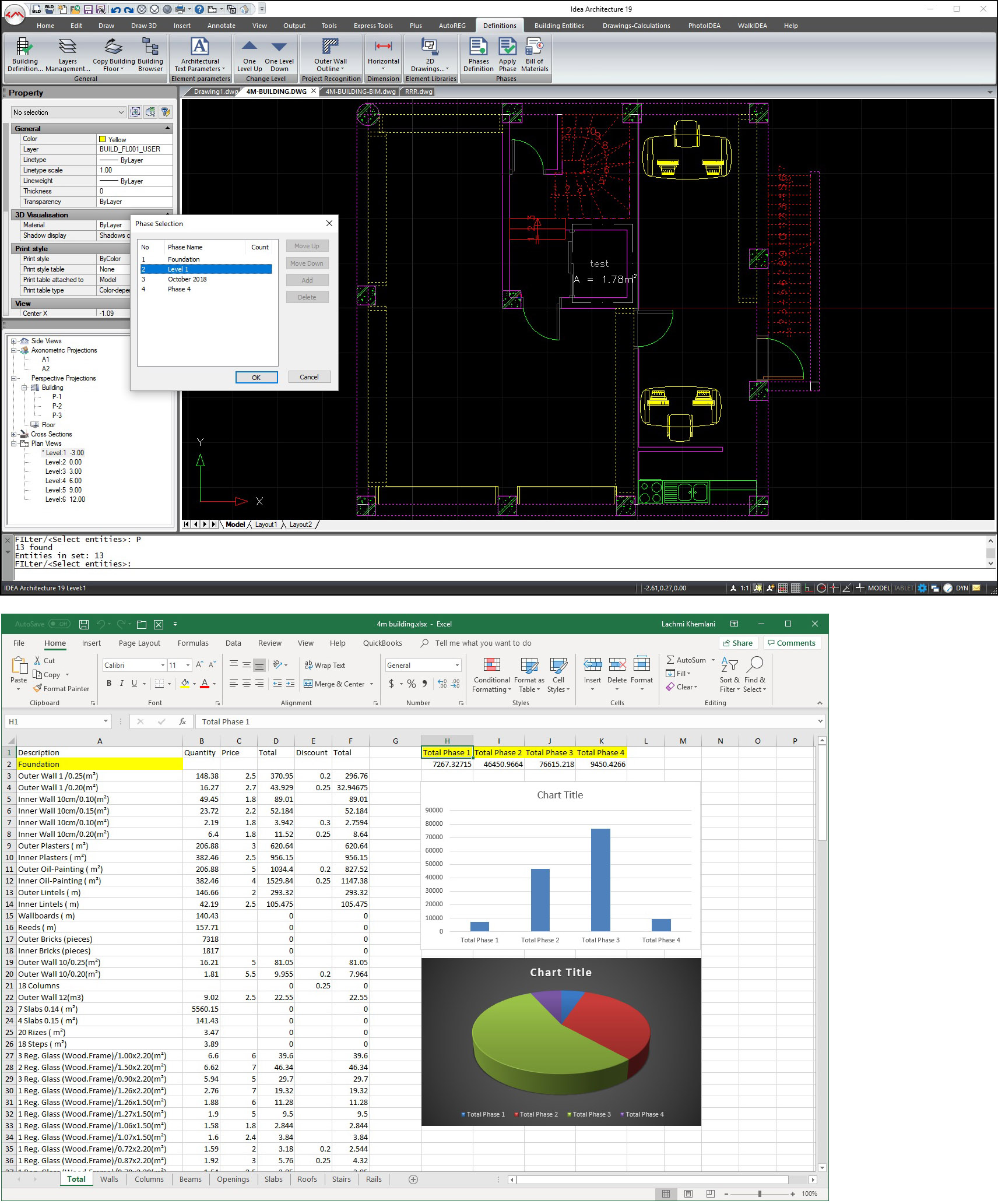

A powerful new feature added to IDEA is the ability to define different construction phases and associate each building element to a phase. A report capturing the BOM (Bill of Materials) for different phases of the project can then be created and exported to Excel, where you can add costing information and create an estimate for the project, illustrating it with charts and graphs (Figure 10). You can also use the phasing data in the Excel spreadsheet for more detailed project planning.

On the interoperability front, IDEA’s native file format of DWG, which is still the de facto standard in the AEC industry, ensures that it can work together easily with the large number of design, engineering, and drawing applications that read and write DWG files. Also, being part of 4M’s BIM suite that includes the FineMEP applications for building engineering and the FineENERGY applications for energy simulation and rating, all of which are built on the same 4DCAD platform, IDEA is well suited to architects working as part of a project team to create a BIM model that includes all the individual disciplinary models.

For interoperability with other BIM applications, IDEA can import and export IFC files, a capability that it has made substantial improvements to in the new release (Figure 11). The fidelity of the IFC models imported and exported from the application is higher, leading to better compatibility with other BIM applications; there are more options in the import and export dialogs for more control on which building elements are imported and exported; and the import process is much faster, often more than the application itself from which the IFC file is exported. (I saw a demonstration of this first-hand with an IFC file exported from Revit. The file took less time to be imported into IDEA than back into Revit.)

The new version of IDEA includes several additional enhancements for drawing, documentation, and site modeling in the form of more options, dialog enhancements, and new commands. Overall, the re-engineered new generation goes a long way towards strengthening its BIM capabilities while retaining its key strengths of AutoCAD compatibility and low cost. IDEA’s interface is not as sophisticated as the more expensive BIM applications by vendors such as Autodesk, Bentley, and GRAPHISOFT, but it is an excellent lower-cost alternative which makes it very popular in several countries around the world that are just starting to transition from CAD to BIM.

On my part, I find it amazing that a small company like 4M headquartered in Greece, which lacks the marketing muscle and development resources of larger companies, can develop such a useful product from an open-source platform that is helpful to millions of AEC professionals around the world who cannot afford the more expensive applications that are prevalent in wealthy countries. 4M may not earn high marks for innovation, but it is way up there when it comes to making a global impact through perseverance and hard work.

Lachmi Khemlani is founder and editor of AECbytes. She has a Ph.D. in Architecture from UC Berkeley, specializing in intelligent building modeling, and consults and writes on AEC technology. She can be reached at lachmi@aecbytes.com.

Have comments or feedback on this article? Visit its AECbytes blog posting to share them with other readers or see what others have to say.

AECbytes content should not be reproduced on any other website, blog, print publication, or newsletter without permission.

Copyright © 2003-2025 AECbytes. All rights reserved.